By Jonathon King

michael israel city and shore magazine

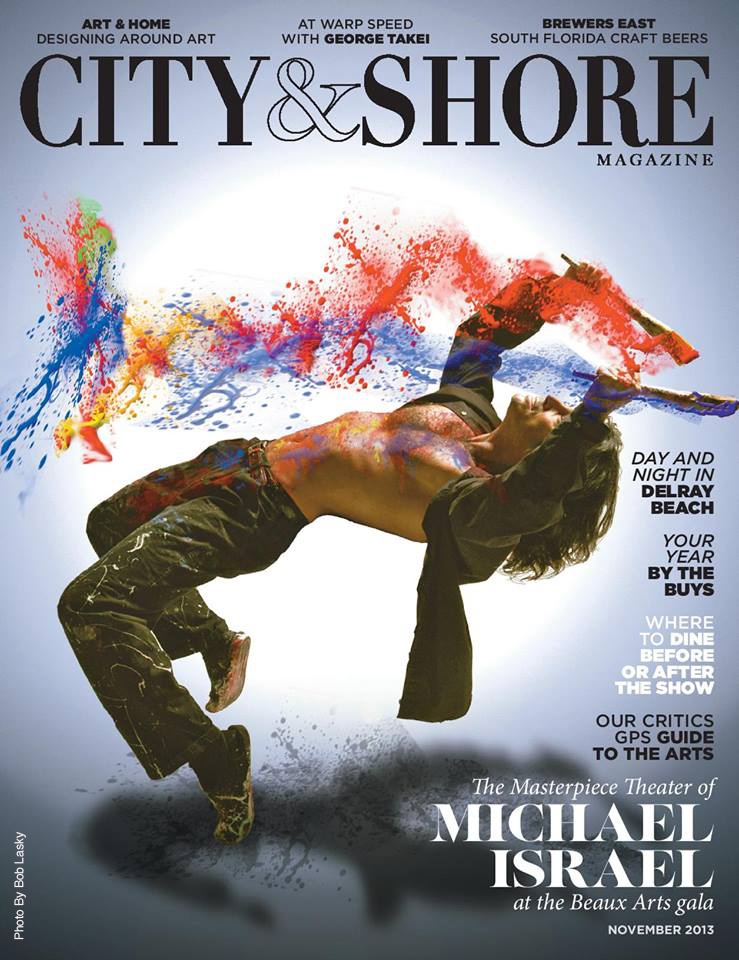

Music — chosen as inspiration, and turned up perhaps a few decibels too loud, meant to envelop you, raise your pulse a few beats, focus your attention.

Paint — vivid in color, and flinging through the air in strings and fat beads from the artist’s brushes before being applied more creatively and circumspectly than the audience might ever realize, to a huge canvas.

Dance — the deft steps and lunges of a trained athlete, the frozen poses of contemplation, and then the attack of a sometimes spinning canvas, seemingly stopped at a random point, but always at a moment of planned choreography.

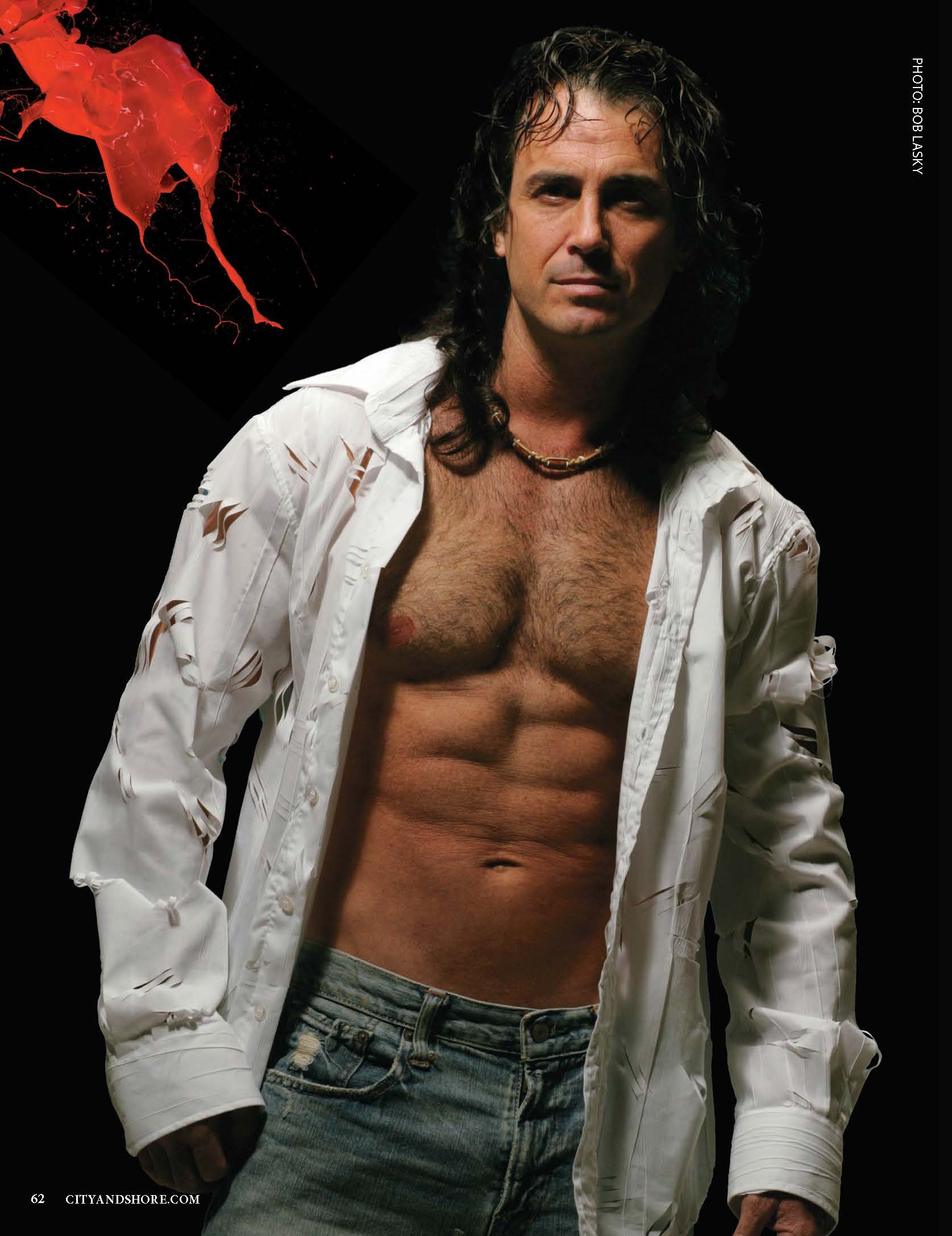

And Showmanship – oh yes, always the showmanship, of the handsome, tuxedo-clad entertainer, his long dark hair and formal attire soon spattered in the paint that creates the image and only adding to the image of instant creativity he weaves like some live magician before your very eyes.

A performance by artist Michael Israel is, in his words, a few minutes of “controlled chaos.”

The results of that chaos may be a stunning portrait of John Lennon or Mahatma Gandhi, a heroic scene of a firefighter’s rescue of a child or a soldier’s salute, a heart-felt likeness of a 5-year-old girl who succumbed to pediatric brain cancer or the rendering of an endangered loggerhead turtle.

“My work is like an instant recognition,” Israel has said. “You don’t have to think about it. You don’t have to analyze it. It goes in through your eyes, it grabs hold of your heart and makes the hair stand up on the back of your neck.

“You know what it’s all about instantly because it’s about what’s inside you, I just bring it out,” he says. “It’s like a mirror.”

Internationally known and with individual paintings that have sold to private collections for as much as $250,000 Israel is better known as a performance artist who actually creates art during his performance.

“He really puts it all together, the music and the lights on stage and it really energizes the audience. When he starts flinging the paint around you go, ‘Whoa, this is different,”’ says Lisa Parks, a contracting executive who saw Israel perform for a benefit for HomeSafe, an organization that protects victims of child abuse and domestic violence. “You’re not really sure what he’s up to with the spinning canvas and all, but then boom, this wonderful painting is suddenly there.”

The music that fills whatever venue Israel performs in is selected by him to add to the overall effect; Ronan, a ballad created by Taylor Swift about a child with cancer, provides the backdrop for his paintings at cancer center appearances. The voice of Enrique Iglesias fills the room when he does his signature Hero performance.

“I’m really trying to create an atmosphere, something that touches the audience,” Israel says. “When everything comes together I’m even getting an adrenaline rush.”

When asked how much rehearsal time he spends before each performance, Israel, who was raised in Hollywood and is now living in Boca Raton, says, “Actually, I’ve been rehearsing for about thirty-five years.”

“I still recall those days when I was six or seven and for whatever reason, I’d be drawing something on the walls of my childhood home. Of course, back then my mother would critique my work … by spanking me.”

Living in a houseboat on the Intracoastal Waterway behind The Diplomat Hotel in Hollywood at the time, Israel says his energy and penchant for constantly creating didn’t make him much of a conventional student.

“I was always in trouble in grade school for not paying attention and for doodling on any blank surface I could find, making my own brand of artwork and designs.”

By his teens, the young, and yes, sometimes starving artist, took an unusual path to hone what would become his signature talent.

“I was working the art shows and weekend sidewalk art fairs making small paintings of anything people brought me whether it was their own live portrait, a photograph of a family member, their pet, a photograph of their home. Pretty much anything,” Israel says.

“You know, you’ve been there with dozens of tents set up on the sidewalks and artists selling all kinds of styles and forms of their artwork. Well, when you’re doing work like that, you can’t make any money unless you do a lot of it. Pretty soon I was doing a sort of speed painting, working on four or five small pieces at a time, jumping from canvas to canvas on my street setup.

“I’d do some five hundred paintings in a weekend. I remember times when I had bandages on my fingers and had a bucket of ice water nearby to soak the pain out of my hands.”

But he also noticed that when he was in the throes of creating multiple pieces of art at the same time, crowds would gather around to watch, not just to see the finished product, but to witness the performance itself.

“I thought, ‘Hey, if I made a buck for all the people who were watching and never sat down to have a painting done, maybe I wouldn’t have to do five hundred. Maybe I could cut it down to two or three hundred.’”

“I also realized I was feeding off the crowd, their energy, their ooohs and ahhs, and their delight in seeing what I was creating in five-minute chunks of time. It was infectious.”

And it was the beginning of an artistic act he has now taken to Presidential Inaugural balls in Washington, D.C., onto the deck of the USS Midway aircraft carrier in San Diego, at the Grimaldi Forum in Monte Carlo, the Olympic Medals stage in Salt Lake City, and to museums and concert stages in dozens of U.S. states, Africa and Canada.

“Where and when it happened, I can’t tell you,” Israel says of the gift and vision and affinity for the creative insight he carries with him.

He says it may have started to come together in grade school when he also started studying martial arts, a dedication for which he has continued for the past 40 years. He would eventually earn a black belt in karate and went to the USKA Grand National Championships at age 17. The athleticism is obvious during his performances both in his graceful movements around the huge and often spinning canvas but also in the concentration he’s able to hold while the music swells and audiences begin to react.

“The karate training really taught me how to focus,” he says. “And it also gave me the ability to meditate and see things with a clear mind.

“While I’m doing the painting and spinning the canvas, I see the image as if I’m seeing it from up above like I’m floating and seeing it from all angles. There are times when I’m nearly finished but I can tell from their reaction that the audience still hasn’t gotten it and I’m thinking, ‘Come on, you gotta be seeing this, and then come the oohs and the ahhs when I finally spin it.”

Though the once doodling child would eventually become an advanced-placement student and graduate of Cooper City High School, even Israel can’t say where the art inspiration came from.

Israel’s father owned and ran amusement rides and was no more of an influence on his son’s love of things artistic than his boat captain mother who cuffed him for drawing on the walls. As a teenager, when Israel had become deeply ensconced in the world of weekend art fairs and street-side presentations to make a living, “my father pretty much told me to get a real job.”

The rift lasted for several years until 2002 when Israel invited his father to an undisclosed event in Washington, D.C. Israel put his father up in a downtown hotel and met him at the venue where he would be performing. As his father stood somewhat perplexed at the black-tie affair, he pointed out to Michael that several dark-suited men in the crowd appeared to be wearing electronic earpieces and seemed highly alert.

“That’s the Secret Service, Dad. I’m the opening act,” he said, handing his father his tickets to G.W. Bush’s 2002 Presidential dinner. “Art just baffled him and sometimes it still baffles me,” Israel says today. “But I guess I’d gotten a real job.”

Obviously, Israel is not the stereotypical artist who spends hours in a grotto, sitting before a canvas painstakingly creating in the conventional mode. And neither is the final painting the sole motivation behind his work.

“The gift of being a human being is art, whether it’s cooking, painting, or music. It’s a combination of knowledge, intellect, and emotion,” Israel says. “I think the greatest masterpieces, whether it’s food or art or science, are the ones that move humanity forward, that empower people. If it’s something that enriches a life, if it feeds the hungry, gives someone a home, then that’s great art whether it’s architecture, or dance or painting.”

Holding that definition in his heart, Israel’s art, and his participation in fundraising for a multitude of causes, has become a mainstay of his career. His aircraft carrier performance raised money for Habitat for Humanity and the Special Ops Warrior Foundation, a benefit in New Orleans was a fundraiser for the Friends of the Fisherman after the Gulf oil-spill disaster, and he created a painting of Payton Wright during his performance to benefit the foundation in Payton’s name that funds research for pediatric brain cancer.

Israel can list more than a hundred charities and foundations — from the Make-a-Wish Foundation to The Shriner’s Hospital, the United Way to Habitat for Humanity, Child Abuse Prevention Center to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation — and myriad other causes that he has been asked to perform for with the hope that his message will inspire others.

He has created his painting of a fireman rescuing a child — his Hero performance — to raise funds for a multitude of charitable agencies across the country.

“What moves me is probably the same thing that moves everybody else. You get that stirring in your stomach; I want to do something. I can’t run out and clean the ocean up, I wish I could, but I don’t have that power. But I can certainly use my talent to bring attention to it, to communicate a message, to empower people, to motivate them, or to give them some hope and that’s a great thing.”